Set in the northern Californian forest in the near-future, Into the Forest focuses on the relationship between two isolated teenaged sisters as they struggle to survive the collapse of society.

Intended more a metaphor or a fable than a prediction, warning, or how-to guide, Into the Forest has been called both poetic and a page-turner. It is the kind of book that some readers read slowly in order to savor every sentence, and that costs other readers a night’s sleep, when they find that they cannot put it down.

Into the Forest has been chosen for a number of college and city-wide reading programs and translated into over a dozen languages, most recently Swedish, Korean, Dutch, and French. The French edition, translated by Josette Chicheportiche and published by Editions Gallmeister in January of 2017, sold over 200,000 copies in less than five years and was awarded a number of literary prizes, including Le Prix de l’Union Interallié, Le Prix des lecteurs du pays de Mortagne, and Le Prix du Marais.

Jean was honored and delighted to learn that a new bookstore in Auvergne has been named Dans la forêt after her novel.

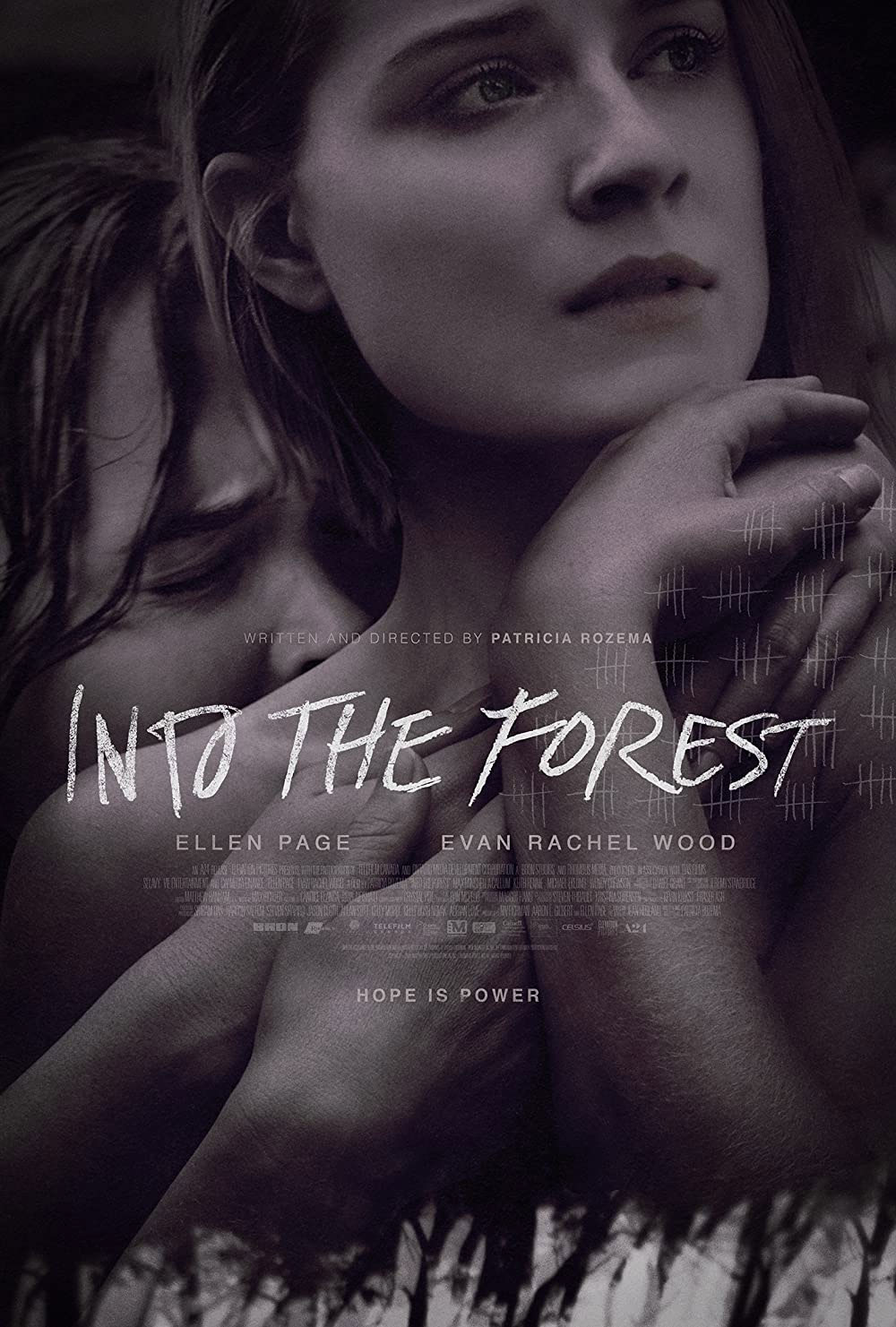

Film

Into The Forest follows teen sisters Eva and Nell in the not-so-distant future as they forage through the forest that surrounds their rural home following the collapse of society. The film adaptation, directed by Patricia Rozema and starring Elliot Page and Evan Rachel Wood, was released theatrically in 2015 and is currently available on DVD and online at various sites including Vudu, iTunes, Amazon, and YouTube.

- Additional info: IMDB

- Downloads: Initial Press Release, Extensive Press Notes

- Toronto Globe & Mail: Elliot Page delivers two much-buzzed films to TIFF

- WeGotThisCovered.com: Into the Forest review by Darren Ruecker

Into the Forest Q&A at the Toronto International Film Festival

Jean on the Red Carpet at the premiere of Into the Forest at the Toronto International Film Festival

Production commenced July 28 in Vancouver and was completed August 28. Thierry Wase-Bailey’s Celsius Entertainment is handling international sales and distribution outside North America. Elevation Pictures picked up Canadian rights, and WME is handling sales for the US. Celsius pre-sold Latin America to Black Castle Group, Greece to Odeon, and Turkey to Calinos and will screen selected scenes at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival. The film is produced with the participation of Telefilm Canada.

Reminiscent of THE ROAD, INTO THE WILD, and the Oscar-nominated WINTER’S BONE, INTO THE FOREST is a mesmerizing and thought-provoking story of hope and despair set against a frighteningly plausible near-future.

The film stars Elliot Page (who also produces), Evan Rachel Wood, Callum Keith Rennie, and Max Minghella. Elliot Page was recently in X-MEN: DAYS OF FUTURE PAST and has previously starred in X-MEN: THE LAST STAND, TO ROME WITH LOVE, INCEPTION, and JUNO. Evan Rachel Wood is next in the WESTWORLD remake. Past credits include THE IDES OF MARCH, WHATEVER WORKS, ACROSS THE UNIVERSE, and THE WRESTLER. Callum Keith Rennie is next in 50 SHADES OF GREY and WARCRAFT. Past credits include BATTLESTAR GALACTICA, 24, THE KILLING, and CALIFORNICATION. Max Minghella is next in HORNS. Past credits include THE INTERNSHIP, THE IDES OF MARCH, and THE SOCIAL NETWORK.

INTO THE FOREST is written and directed by Patricia Rozema (MANSFIELD PARK, GREY GARDENS), adapted from the novel by Jean Hegland, and produced by Niv Fichman (ENEMY, THE RED VIOLIN, BLINDNESS), Elliot Page, and Aaron L. Gilbert (WELCOME TO ME, TUMBLEDOWN, THE MASTER CLEANSE). Executive producers Kelly Bush Novak, Jason Cloth, Sriram Das (NOVEMBER MAN), Haroon Saleem, and Steven Shapiro.

Elliot Page & Evan Rachel Wood discuss INTO THE FOREST

Max Richter has signed on to score the upcoming futuristic drama Into the Forest. The film is directed by Patricia Rozema (Mansfield Park, When Night Is Falling) and stars Elliot Page, Evan Rachel Wood, Callum Keith Rennie and Max Minghella. The movie based on the novel of the same title by Jean Hegland is set in the not-too-distant future and follows two sisters who must rely on one another as society crumbles around them and their forest home. Rozema has written the screenplay. Page is also producing the project with Niv Fichman (Enemy, The Red Violin, Blindness) and Aaron L. Gilbert (A Single Shot, Welcome to Me). Into the Forest is currently in post-production and is expected to premiere in 2015.

Richter’s recent projects also include the historical drama Testament of Youth, which is set to open in the UK next month, as well as the dramatic thriller Escobar: Paradise Lost, which will be released on VOD on December 16 and open in select theaters on January 16. The composer is also expected to return for the second season of HBO’s The Leftovers. A soundtrack featuring the music from the first season was just released last week and the composer performed his music from the hit series live for the first time last night in New York.

Into the Forest’s Elliot Page: “Financing a Movie with Two Female Leads is Just Harder” (The Hollywood Reporter)

Elliot Page and Evan Rachel Wood are diving into futuristic drama “Into the Forest,” starring as sisters in the film adaptation of Jean Hegland’s novel of the same name.

Page is also producing. Patricia Rozema (“Grey Garden,” “Mansfield Park”) will direct from her adapted screenplay.

Story centers on sisters struggling to survive after the collapse of society in the not-too-distant future. The novel, published in 1998, was set in Northern California with the teen siblings living in a forest home over 30 miles from the nearest town and several miles away from their nearest neighbor.

Besides Page, ID-PR founder and CEO Kelly Bush Novak and Sriram Das are set to produce. Haroon (Boon) Saleem is exec producing and Kristina Sorensen is associate producer.

Page recently wrapped on “X-Men: Days of Future Past” and is attached to Fox’s “Queen and Country.”

Wood will next be seen in “Charlie Countryman” opposite Shia LaBeouf and “A Case of You” opposite Justin Long. She also recently finished filming Andrew Fleming’s “Barefoot.”

Page is represented by WME, Barnes Morris Klein Mark and Yorn, and Vie Entertainment. Wood is represented by CAA. Rozema is represented by CAA.

Evan Rachel Wood, Patricia Rozema, Michael Eklund, Callum Keith Rennie, and Jean Hegland at the Toronto International Film Festival red carpet

Into The Forest is admirably defiant of many tropes that spring up in most apocalyptic stories, emphasizing its small character moments over large dramatic ones. Even the fact that it takes place in the forest gives it more of an Into the Woods vibe, visually and thematically, than, say, a Mad Max one. When it does require some scenes to move the plot along, these tend to be not nearly as compelling as the quieter scenes, like when the sisters decide to get drunk, or watch videos of their parents. This is where the main interest and heart of the film, and of director Patricia Rozema, seem to be; everything else is texture, although the texture set by the visual and musical tone provides an appropriate feeling of balance being lost.

—Darren Ruecker, for wegotthiscovered.com

Elliot Page talks about being a lesbian actress at the Toronto International Film Festival

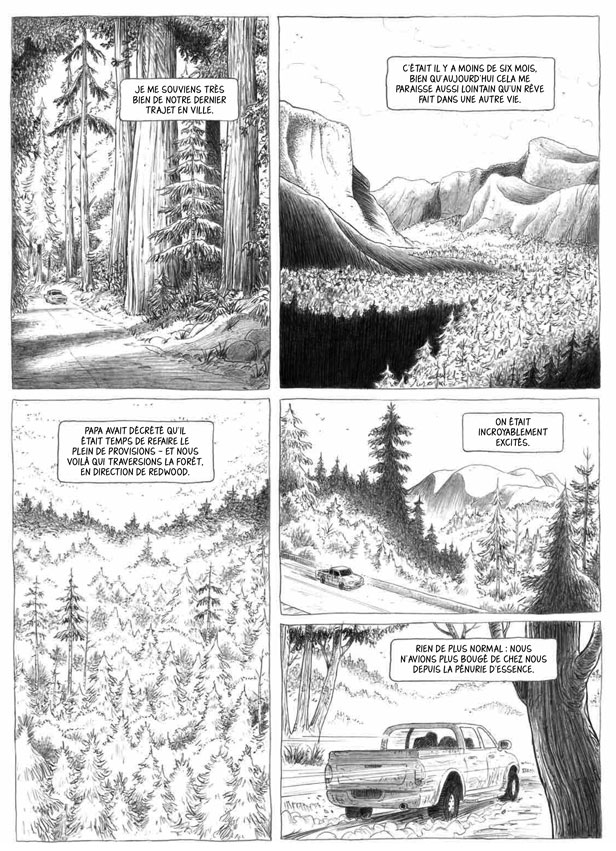

Graphic Novel

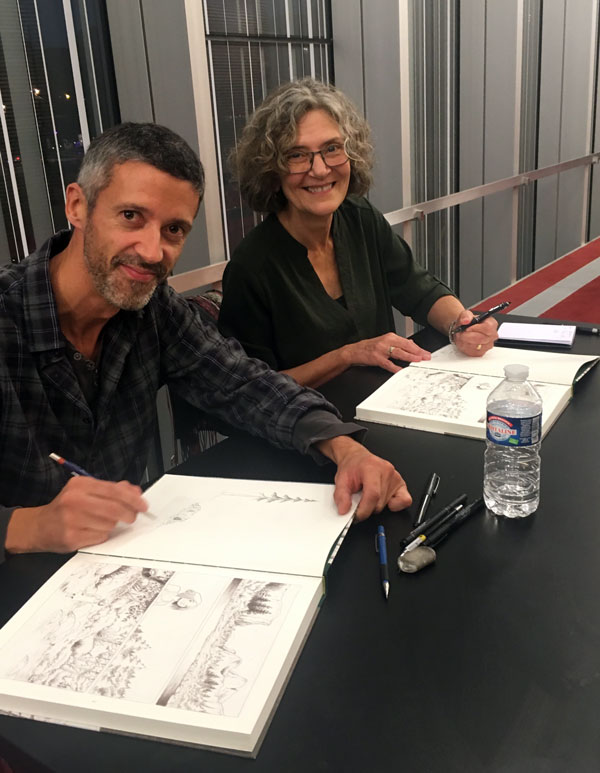

Into the Forest was adapted into graphic-novel form by French cartoonist Lomig in 2019. The beautifully-rendered adaptation can be purchased through Editions-Sarbacane.com from a number of French outlets.

Reviews

Hegland’s powerfully imagined first novel will make readers thankful for telephones and CD players while it underscores the vulnerability of lives dependent on technology. The tale is set in the near future: electricity has failed, mail delivery has stopped and looting and violence have destroyed civil order. In Northern California, 32 miles from the closest town, two orphaned teenage sisters ration a dwindling supply of tea bags and infested cornmeal. They remember their mother’s warnings about the nearby forest, but as the crisis deepens, bears and wild pigs start to seem less dangerous than humans. From the first page, the sense of crisis and the lucid, honest voice of the 17-year-old narrator pull the reader in, and the fight for survival adds an urgent edge to her coming-of-age story. Flashbacks smartly create a portrait of the lost family: an iconoclastic father, artistic mother and two independent daughters. The plot draws readers along at the same time that the details and vivid writing encourage rereading. Eating a hot dog starts with “the pillowy give of the bun,” and the winter rains are “great silver needles stitching the dull sky to the sodden earth.” If sometimes the lyricism goes a little too far, this is still a truly admirable addition to a genre defined by the very high standards of George Orwell’s 1984 and Russell Hoban’s Ridley Walker.

This beautifully written and often profoundly moving novel by gets mired early in a murderously sluggish pace as patient readers wait for something to happen.

We don’t mind at first because so much has already happened to the two sisters: Nell, 17, who narrates “Into the Forest” by keeping a “chronicle of this time” on one of the few remaining pieces of notebook paper in the area, and Eva, 18, a gifted ballet dancer who practices to a metronome because there is no electricity.

Somewhere in the near future, a dozen miles outside a town like Cloverdale or Red Bluff or Redding (it’s called “Redwood” in the book), the two sisters try to carry on with life in their family cabin, gradually realizing that the worst has happened.

Electricity sputtered to a halt long ago, as did telephone service and running water. Mail delivery also slowed to a stop. Banks and businesses in town closed. Planes stopped flying. Stores were looted and abandoned. Gas became invaluable, as did antibiotics, plastic bags, working batteries and dependable (not rumored) word from “the outside.”

If it all sounds too outlandish Northern California writer Jean Hegland and fictional to be possible, Nell recalls “how quickly everyone adapted” in another time, when “people beyond our forest” learned how “to drink bottled water, drive on overcrowded freeways and deal with the automated voices that answered almost every telephone. Then, too, they cursed and complained, and soon adjusted, almost forgetting their lives had ever been any other way.”

But now, everyone knows something is really wrong — even before batteries ran out of energy and radios sputtered news of a vague, distant war “taking place to protect freedoms, to defend a way of life the politicians promised,” writes Nell. “Some people said it was that war that caused the breakdown.”

“Breakdown” is a nice word for what’s going on. Word has come to Redwood that the war never ended; the overseas currency market has failed; a paramilitary group has bombed the Golden Gate Bridge; an earthquake has caused meltdown in one of California’s nuclear reactors; overuse of pesticide has ruined farmlands; the ozone is full of holes; welfare has crumbled; schoolchildren are shooting each other; and outbreaks of once-curable disease (strep, meningitis) are killing multitudes.

At the cabin where Nell and Eva’s mother gave them an excellent home-school education before her death from cancer, and where their father died in a chain-saw accident while trying to “make do,” the two sisters struggle to shore up the life they once took for granted. “I remember emptying wastebaskets that would seem like fortunes now,” says Nell, “baskets filled with cardboard cores of toilet paper rolls, with used tissues, broken pencils, twisted paper clips, sheets of crumpled notebook paper and empty plastic bags.” This is where the story bogs down. Aside from preserving the past, meeting an unexpected visitor or two and considering rumors that civilization has returned elsewhere, they experience nothing but worry and longing, grief for their parents and the vagaries of a make-do life. As Eva dances compulsively “to the dead, ungiving rhythm of the metronome . . . her dancing finer than ever,” Nell compulsively reads the encyclopedia, her only way to study for an entrance exam that one day, when the “breakdown” ends, will admit her to Harvard.

We do find it intriguing that when Nell gets to the word “amnesia,” she learns that during prolonged loss of memory, amnesiacs may enter a “fugue state” — a new life unrelated to the previous one. Nell looks out at the empty yard and thinks, “This is our fugue state — the lost time between the two halves of our real lives.” That, we realize as the pace gradually quickens, is what this exquisitely conceived book is all about.

Somewhere “out there,” destiny awaits everyone; wholeness is for those who choose not to forget what is deeply, possibly human. To watch Nell and Eva use the current “breakdown” to move toward a chosen future is to understand the depth and great importance of Hegland’s message. After all, readers of this book, as Nell points out, are adjusting to the first stages of the “breakdown” already.

—Patricia Holt, San Francisco Chronicle

Nell and Eva are two young sisters who are not quite women but no longer children. During the delicate years of teenage emotional and physical maturity, the world around them collapses from economic failure and the sisters find themselves completely isolated from civilization.

Nell is the younger of the two and has been struggling with losing the close relationship with her sister when Eva finds an obsessive passion for dancing. They live with their parents in the last home on a rural road, miles away from town. Although the girls are home-schooled, they venture weekly into town with their father and forge new and exciting friendships with local teenagers in the town square.

Shortly after their mother passes away from cancer, signs of an economic collapse begin to emerge with regular power outages, gas shortages and constant news of war, plagues and rioting on the radio and television. Eventually, the power turns off and never comes back on. With no gas for the truck, the girls and their father are unable to return to town and the girls lose the connections they had made over the summer.

Using food harvested from their garden, they are able to can and store a good amount of food to last through a winter. Both of the girls believe with all of their heart that everything will return to normal soon. Nell will be able to go to Harvard and so she continues to study by candlelight, reading each and every entry in the family’s collection of encyclopedias. Eva continues to dance without music, convinced that once order is restored she will join a dance troupe in a big city.

Their dreams come to a close when their father is fatally wounded in the woods while felling trees. The girls are alone with no one to guide them or give them hope. Yet they cling to what little strength they have left and dare to keep their dreams alive.

After Nell almost leaves her sister to follow the dream of her boyfriend who shows up months later at her door, and after Eva is brutally raped by a stranger, the girls slowly succumb to the realization that things are not going to change. They need to take drastic steps to take care of themselves and forget their dreams. Nell lets go of her childish crush and Eva stops dancing. Together they work the land, learn about the forest and what it can provide for them and store food for the winter.

After Eva’s baby comes, the result of her painful rape, the girls decide to take one last step. They burn their home and move to the forest where they feel comfortable.

I really enjoyed the ending because I understood it. I don’t think I would have been able to burn the house down because it offered protection and it also contained things they could use. But the sisters saw the house as something holding them back, preventing them from moving on. It was the last thing which kept them tethered to the dreams of old, the dreams which would never come to fruition.

With the house gone, they could let go of their old hopes and dreams and were free to create new ones. The house also made them targets to looters and rapists and so the destruction of their home was a form of protection, both physically and emotionally.

Into the Forest can be seen not only as a coming of age story but as a very relevant book as far as the economic crisis is concerned. This is a plausible event which could happen, especially in today’s eerily similar circumstances. The book was written in 1998 almost as if the author could sense what was to come. The book succeeded in making me cringe with fear and foreboding!

I enjoyed this book and would read something else by the author in a heartbeat.

—Rebecca Skane, Seacoast Online

Brisk, feminist, contemplative first novel about the end of contemporary civilization and the survival of two sisters. Hegland is vague about civilization’s downfall. She places a wife, a husband, and their two daughters, Eva and Nell, on 50 acres of second-growth redwood forest in northern California—the idea seeming to be that since the location is remote to begin with, news of the outside world would filter in slowly. There’s a war somewhere, and ever more virulent strains of viruses rage through the population; then, suddenly, there’s no more food available in stores, no more gasoline, no more television. The mother dies; the father pushes his dreamy daughters to learn such humble skills as gardening and canning. In the best scene, the father’s chain saw kicks back and cuts him, and his daughters are helpless, unable to do more than watch as he bleeds to death. They bury him where he lies. Slowly, because the alternative is starvation, Nell learns the wisdom of the forest: killing a wild sow with a rifle she barely knows how to fire, using herbs for medicines and tea, gathering acorns to pound into flour. A boy comes to take Nell away, but she cannot leave Eva; though sisters by birth, Hegland turns the girls into lovers—and ideologically pure lovers, at that. Mystically, they both produce milk to nurse Eva’s son, the product of a rape by a passing thug. Fearful of more such violence, the sisters burn down their father’s house and take up housekeeping in a mammoth redwood stump. They’ve learned nature’s lessons and, purified, are prepared for humankind’s great destiny: to live in the woods like animals. A little apocalypse goes a long way. Beautifully written, however, and Hegland’s knowledge of organic gardening, fruit drying, etc., is impeccably authentic.

Jean Hegland’s debut novel Into the Forest, about two sisters living alone in a Northern California woodland after a general disaster has robbed them of all the things of civilization, is beautifully written, moving, and the kind of tale one has to call “wise”—a small masterpiece, in fact. First released by an American small press in 1996, it was reissued by a major New York publisher in late 1997, and now reaches Britain as a B-format paperback original. It’s not described as science fiction, but the publishers compare it to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and quote Publishers Weekly to the effect that it is “a truly admirable addition to a genre defined by George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker“—which is all familiar coded language for what readers of this magazine might understand as “literary sf.” But it has not been reviewed, so far, in Locus or in any other genre periodical that I have seen.

Aside from its intrinsic virtues as a very readable text by a beguiling new voice, I find it doubly interesting: as yet another instance of a serious sf work presented as “mainstream,” and as a clear example of a particular sub-genre which has long fascinated me, namely “California sf.” The comparisons to Atwood, Orwell and Hoban are all somewhat wide of the mark, for what in effect this is (whether the author realizes it or not) is a feminine rewrite of George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides (1949), with echoes of Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home (1985). Jean Hegland makes no specific reference to Stewart or Le Guin, and it may well be that she has never read them (Stewart in particular is sadly lacking in honour in his home country these days), but she acknowledges as one of her sources a book called The Way We Lived: California Indian Reminiscences, Stories, and Songs. What happens in her finely detailed and deeply felt narrative is that the two teenage sisters, bereft of parents, schooling and all the gadgetry of modern civilization (there are explicit “farewells” to electricity, telephones, automobiles, refrigerators, computers), re-adopt the foraging lifestyle of the California Indians of old: they take to the forest and learn to accept its bounty, recreating a way of survival in that land which, after all, sufficed for 10,000 years before the coming of Europeans. In short, it is another “apology to Ishi” novel, as much of the best California sf tends to be.

Ishi, for those who may not be familiar with his true-life tale, was the stone-age California Indian who walked out of the northern hills one day in 1911, having lived alone for several years following the deaths of all other members of his tribe. His people had had no contact, other than the violent sort, with white American culture, and by the time he reached “civilization” there was no one left who spoke his language. A few years earlier he probably would have been killed, or would have died, rapidly and unmourned, from the white man’s diseases; but luckily, by 1911, there were a few people who were capable of understanding him and providing him with a home and protection against the world. They were Professor A. L. Kroeber and his associates in the recently-founded anthropology department at the University of California, San Francisco. For about five years, before an unfamiliar disease did claim him, Ishi became a sort of living exhibit at the university and taught his protectors much about his extinct tribe’s way of life. The story is told in the book Ishi in Two Worlds (1960) by Theodora Kroeber—herself only a child in Ishi’s time, but later to marry Alfred Kroeber and become the mother of Ursula Le Guin. The narrative (although not specifically Mrs Kroeber’s book) also formed the basis of a movie, The Last of His Tribe (1991), which starred the Native American actor Graham Greene (best known from Dances with Wolves) as Ishi and John Voight as Kroeber.

Ishi’s story seems inherently science-fictional, almost a tale of time-travel, involving alien conquest and a stranger in a strange land. He came, quite literally, from the stone age, his people never having adopted agriculture or the working of metals, and he found himself living in a 20th-century metropolis of telegraphs and trolleybuses and more people than he could ever have imagined existed on the face of the Earth. No one spoke his language (apart from a few book-learned words that the anthropologists were able to acquire), and no one knew the songs and tales and myths of his people—all were utterly gone. Those people had survived deep in the woods, virtually unknown and unchanged, on the margins of Californian society through all the years of Spanish and Mexican rule, and through a further 60 years in which their home had been incorporated into something called the United States of America, Land of the Free. When they did come into contact with white settlers they were hunted down and killed—to the point where they had been assumed to be extinct for decades. But Ishi survived to tell his story; and it is a profoundly moving story, perhaps the greatest of all American stories.

“The last wild Indian” became a nine-day wonder in San Francisco, and one of the local writers who possibly met him and was influenced by his life-story was Jack London, arguably the father of California sf. In 1911, the year of Ishi’s appearance, London wrote his novella “The Scarlet Plague” (ironically, first published in England, in the appropriately-named London Magazine, in June 1912; it has just been reprinted in David Hartwell’s big anthology The Science Fiction Century, Tor, 1997; Robinson, UK, 1998, £14.99). In this story London imagines an old man, in a ruined, reforested San Francisco of the 21st century, trying to explain to his uncomprehending “tribal” grandchildren what life was like back in the days of automobiles and airplanes. The youths, more interested in hunting with their bows and arrows, regard him tolerantly as a rambling old eccentric. I have never seen it suggested anywhere, but I suspect that London created his old hero as a kind of “inverted Ishi”—a representative of our civilization who is thrust into a hunter- gatherer society where nobody can possibly understand him. Over 30 years later George R. Stewart took this idea and turned it into a full-length novel, Earth Abides. Born in 1895 and educated at the University of California, Stewart certainly would have read Jack London, but whether or not he was consciously emulating London there can be no dispute that he had the real-life tale of Ishi very much in mind: his hero is called Isherwood Williams, or “Ish” for short, and he drives out of those same Northern California mountains to find a world where almost everyone has died as the result of a mysterious new plague. Ish’s attempts, over the next 60 years, to rebuild civilization result in a new tribal society, all literacy and high technology forgotten, and eventually he dies, an old man in his 80s babbling of incomprehensible things…

In my view, Stewart’s book is the finest work of California sf, and the greatest “apology to Ishi.” Apart from anything else, it is an excellent piece of ecological science fiction—Stewart knew the land, the animals and the natural phenomena, and wrote about the likely consequences of a large-scale disaster more authoritatively than anyone else has done in fiction. “Ecology,” surely an unfamiliar concept to the general public in the 1940s, has become a global buzzword since Stewart wrote about it—not only in Earth Abides but in his more mundane California-set disaster novels, Storm (1941) and Fire (1948), and various other books—and of course it remains an enduring theme in California sf, from Ray Bradbury’s classic The Martian Chronicles (in which California is reimagined as the Red Planet, complete with Ishi-like native inhabitants viewed, as it were, from the corner of the eye) to the two recent trilogies by Kim Stanley Robinson, The Wild Shore (1984), The Gold Coast (1988), and Pacific Edge (1990); and Red Mars (1992), Green Mars (1993), and Blue Mars (1996)—the former very explicitly about California history and possibility, and the latter featuring Mars as a California surrogate once more (a few British examples excepted, most of the definitive “Mars novels” in sf have been written by California-based writers).

And then of course there is Ursula Le Guin—famously a resident of Portland, Oregon, but born and raised in California. As the daughter of Alfred and Theodora Kroeber, she must have grown up with the story of Ishi in her very bones, and although I am not aware that she has made any reference to it in her fiction (nor to Stewart’s masterpiece in her non-fiction), her major book Always Coming Home may be viewed as another version of the same cyclical, Ishi-inspired story. It is set in Northern California, centuries hence, but instead of recounting the fall of our own civilization and the very beginnings of the new (as do London, and Stewart, and Jean Hegland) it tells of the long-term consequences: it is a utopian account, recollected in tranquillity, of a neo-tribal society based on California Indian ways—in short, it is Ishi vindicated.

So Hegland’s book appeals in part because it is a pure example of this tradition—the major tradition, or cluster of traditions, of its author’s home state. She does not mention Ishi, although she evokes two real-life female Ishi substitutes—the so-called Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island, who lived in solitude for nearly 20 years after her tribe had been deported (and eventually was “rescued” only to find, in the usual cruel irony, that all her people were dead or dispersed—she herself died a few days later); and Sally Bell, a California Indian who, at the age of about 90, left an account of the long-ago massacre of her tribe by whites and of how, in particular, she had run off into the woods with her sister’s heart in her hands. Hegland weaves these two unbearably sad stories into her narrative, briefly and judiciously, making of her novel an apology to the Lone Woman, an apology to Sally Bell.

Nor does Jean Hegland (who, by the way, is never preachy or “New Agey”) make mention of Stewart or Le Guin, or any other work of California sf—apart from Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, which features in a list of books her teenage narrator has read—but an outstanding contribution to California sf is what her novel most certainly is.

—David Pringle, Interzone

Praise

“…Beautifully written and often profoundly moving…To watch Nell and Eva use the current ‘breakdown’ to move toward a chosen future is to understand the breadth and great importance of Hegland’s message.”

— Patricia Holt, San Francisco Chronicle

“Hegland’s story—imagistic, lyrical and ecologically intelligent—challenges the reader to imagine the choices available should our technology fail us….Hegland writes with a poet’s sensitivity and depth….”

— Alice Evans, The Oregonian

“Into the Forest is so thrillingly written that it becomes a page turner from its very start….an exhilarating, visionary novel…”

— Elizabeth Hand, Fantasy and Science Fiction

Hegland “has the ability to make the giant redwood trees seem palpable, to allow readers to breathe in the smell of the rich humus on the floor of the forest.”

— Lisa S. Nussbaum, Library Journal

“This reviewer is better known for acerbity than unqualified recommendations, but I do now suggest you go straight out and buy this book.”

— Diane de Avalle-Arce, Small Press

“The plot draws readers along at the same time that the details and vivid writing encourage rereading….a truly admirable addition to a genre defined by the very high standards of George Orwell’s 1984 and Russell Hoban’s Ridley Walker.

— Publishers Weekly

“Hegland’s sweet and sadly elegiac tale is an engrossing coming-of-age adventure.”

— Whitney Scott, Booklist

“A real gem, Hegland’s first novel…has all the charm and depth of such favorites as Snow Falling on Cedars and Cold Sassy Tree.”

— Marge Harrington, Austin American-Statesman

“Hegland’s portrayal…overflows with sensitivity and compassion.”

— Paul Rhodes, Yorkshire Evening Press

“By rights this tale of the complete collapse of society and technology should be a depressing story, but the author has turned it onto a triumph.”

— Barbara Howe, Dorset Evening Echo

“….a beguiling and haunting tale of redemption.”

— Evie Arup, Independent on Sunday

“Hegland’s debut novel…is beautifully written, moving, and the kind of tale one has to call ‘wise’—a small masterpiece, in fact.”

— David Pringle, Interzone

Book Group Guide

- Into the Forest seems to convey that the stripped-down life of a hunter-gatherer would be better for us as a species. What Nell and Eva do is clearly right for them. Would it be right for people in general? For women? Is it a tenable ideal for any but the very young, very fit, and very adaptable?

- Does the lifestyle the sisters adopt in Into the Forest imply or require an abandonment of the whole notion of “advanced civilization?”

- The Women’s Review of Books said of Into the Forest: “Cultural trauma forces the heroines to inhabit and regard their world in radical new ways, [as] recipients of wisdom they did not want but are better off for having.” Do you agree with this? Why or why not?

- How would you answer the question raised by this novel and posed in The Sunday Oregonian: “Where are we heading, and do we know how to survive with our humanity intact if we continue in this direction?”

- Before razing the house in which they had spent their entire lives and turning to the forest for all their necessities, Nell chooses three books to take with her: Native Plants of Northern California for Eva since it may have already saved her life; a book of stories of those who had lived in the forest for Burl; and the encyclopedia’s index for herself. In choosing the index she says, “I could not save all the stories, could not hope to preserve all the information—that was too vast, too disparate, perhaps even too dangerous. But I could take the encyclopedia’s index, could try to keep that master list of all that had once been made or told or understood.” If you could take only one item from your current existence into the future, and that one item was a book, which one would you choose and why? Why do you think that Hegland would choose to describe the retaining of information as “too dangerous?”

- Some of the most poignant moments of the story are found in minor details. Reading Into the Forest will forever change the way you think about a teabag, a scrap of paper, a metronome, an acorn, or a chocolate kiss candy. It will forever change your thinking about dreams and days of the week. Which of these affected you most? What other examples struck your sensibilities?

- Above all, Into the Forest is a story about the boundaries and possibilities of sisterhood. Do you feel a comparable story could have been written about a relationship between a brother and sister or two brothers?

- What kind of childhood do you think Eva’s baby will have? If technology and society were to return to advanced states, how might the child adapt to leaving the forest?

- If your “technologically-based” lifestyle were to evolve into a “nature-based” lifestyle, how do you think you would survive? What would you enjoy? What conveniences would you most miss?

Excerpt

It’s strange, writing these first words, like leaning down into the musty stillness of a well and seeing my face peer up from the water—so small and from such an unfamiliar angle I’m startled to realize the reflection is my own. After all this time a pen feels stiff and awkward in my hand. And I have to admit that this notebook, with its wilderness of blank pages, seems almost more threat than gift—for what can I write here that it will not hurt to remember?

You could write about now, Eva said, about this time. This morning I was so certain I would use this notebook for studying that I had to work to keep from scoffing at her suggestion. But now I see she may be right. Every subject I think of—from economics to meteorology, from anatomy to geography to history—seems to circle around on itself, to lead me unavoidably back to now, to here, today.

Today is Christmas Day. I can’t avoid that. We’ve crossed the days off the calendar much too conscientiously to be wrong about the date, however much we might wish we were. Today is Christmas Day, and Christmas Day is one more day to live through, one more day to be endured so that someday soon this time will be behind us.

By next Christmas this will all be over, and my sister and I will have regained the lives we are meant to live. The electricity will be back, the phones will work. Planes will fly above our clearing once again. In town there will be food in the stores and gas at the service stations. Long before next Christmas we will have indulged in everything we now lack and crave—soap and shampoo, toilet paper and milk, fresh fruit and meat. My computer will be running, Eva’s CD player will be working. We’ll be listening to the radio, reading the newspaper, using the Internet. Banks and schools and libraries will have reopened, and Eva and I will have left this house where we now live like shipwrecked orphans. She will be dancing with the corps of the San Francisco Ballet, I’ll have finished my first semester at Harvard, and this wet, dark day the calendar has insisted we call Christmas will be long, long over.

“Merry semi-pagan, slightly literary, and very commercial Christmas,” our father would always announce on Christmas morning, when, long before the midwinter dawn, Eva and I would team up in the hall outside our parents’ bedroom. Jittery with excitement, we would plead with them to get up, to come downstairs, to hurry, while they yawned, insisted on donning bathrobes, on washing their faces and brushing their teeth, even—if our father was being particularly infuriating—on making coffee.

After the clutter and laughter of present-opening came the midday dinner we used to take for granted, phone calls from distant relatives, Handel’s Messiah issuing triumphantly from the CD player. At some point during the afternoon the four of us would take a walk down the dirt road that ends at our clearing. The brisk air and green forest would clear our senses and our palates, and by the time we reached the bridge and were ready to turn back, our father would have inevitably announced, “This is the real Christmas present, by god—peace and quiet and clean air. No neighbors for four miles, and no town for thirty-two. Thank Buddha, Shiva, Jehovah, and the California Department of Forestry we live at the end of the road!”

Later, after night had fallen and the house was dark except for the glow of bulbs on the Christmas tree, Mother would light the candles of the nativity carousel, and we would spend a quiet moment standing together before it, watching the shepherds, wise men, and angels circle around the little holy family.

“Yep,” our father would say, before we all wandered off to nibble at the turkey carcass and cut slivers off the cold plum pudding, “that’s the story. Could be better, could be worse. But at least there’s a baby at the center of it.”

This Christmas there’s none of that.

There are no strings of lights, no Christmas cards. There are no piles of presents, no long-distance phone calls from great-aunts and second cousins, no Christmas carols. There is no turkey, no plum pudding, no stroll to the bridge with our parents, no Messiah. This year Christmas is nothing but another white square on a calendar that is almost out of dates, an extra cup of tea, a few moments of candlelight, and, for each of us, a single gift.

Why do we bother?

Three years ago—when I was fourteen and Eva fifteen—I asked that same question one rainy night a week before Christmas. Father was grumbling over the number of cards he still had to write, and Mother was hidden in her workroom with her growling sewing machine, emerging periodically to take another batch of cookies from the oven and prod me into washing the mixing bowls.

“Nell, I need those dishes done so I can start the pudding before I go to bed,” she said as she closed the oven door on the final sheet of cookies.

“Okay,” I muttered, turning the next page of the book in which I was immersed.

“Tonight, Nell,” she said.

“Why are we doing this?” I demanded, looking up from my book in irritation.

“Because they’re dirty,” she answered, pausing to hand me a warm gingersnap before she swept back to the mysteries of her sewing.

“Not the dishes,” I grumbled.

“Then what, Pumpkin?” asked my father as he licked an envelope and emphatically crossed another name off his list.

“Christmas. All this mess and fuss and we aren’t even really Christians.

“Goddamn right we aren’t,” said our father, laying down his pen, bounding up from the table by the front window, already warming to the energy of his own talk.

“We’re not Christians, we’re capitalists,” he said. “Everybody in this whangdanged country is a capitalist, whether he likes it or not. Everyone in this country is one of the world’s most voracious consumers, using resources at a rate twenty times greater than that of anyone else on this poor earth. And Christmas is our golden opportunity to pick up the pace.”

When he saw I was turning back to my book, he added, “Why are we doing Christmas? Beats me. Tell you what—let’s quit. Throw in the towel. I’ll drive into town tomorrow and return the gifts. We’ll give the cookies to the chickens and write all our friends and relations and explain we’ve given up Christmas for Lent. It’s a shame to waste my vacation, though,” he continued in mock sadness.

“I know.” He snapped his fingers and ducked as though an idea had just struck him on the back of the head. “We’ll replace the beams under the utility room. Forget those dishes, Nell, and find me the jack.”

I glared at him, hating him for half a second for the effortless way he deflected my barbs and bad temper. I huffed into the kitchen, grabbed a handful of cookies, and wandered upstairs to hide in my bedroom with my book.

Later I could hear him in the kitchen, washing the dishes I had ignored and singing at the top of his voice,

tried to smoke a rubber cigar.

It was loaded, and it exploded,

higher than yonder star.”

The next year even I wouldn’t have dared to question Christmas. Mother was sick, and we all clung to everything that was bright and sweet and warm, as though we thought if we ignored the shadows, they would vanish into the brilliance of hope. But the following spring the cancer took her anyway, and last Christmas my sister and I did our best to bake and wrap and sing in a frantic effort to convince our father—and ourselves—that we could be happy without her.

I thought we were miserable last Christmas. I thought we were miserable because our mother was dead and our father had grown distant and silent. But there were lights on the tree and a turkey in the oven. Eva was Clara in the Redwood Ballet’s performance of The Nutcracker, and I had just received the results of my Scholastic Aptitude Tests, which were good enough—if I did okay on the College Board Achievement Tests—to justify the letter I was composing to the Harvard Admissions Committee.

But this year all that is either gone or in abeyance. This year Eva and I celebrate only because it’s less painful to admit that today is Christmas than to pretend it isn’t.

It’s hard to come up with a present for someone when there is no store in which to buy it, when there is little privacy in which to make it, when everything you own, every bean and grain of rice, each spoon and pen and paper clip, is also owned by the person to whom you want to give a gift.

I gave Eva a pair of her own toe shoes. Two weeks ago I snuck the least battered pair from the closet in her studio and renovated them as best I could, working on them in secret while she was practicing. With the last drops of our mother’s spot remover, I cleaned the tattered satin. I restitched the leather soles with monofilament from our father’s tackle box. I soaked the mashed toe boxes in a mixture of water and wood glue, did my best to reshape them, hid them behind the stove to dry, and then soaked and shaped and dried them again and again. Finally I darned the worn satin at the tips of the toes so that she could get a few more hours of use from them by first dancing on the web of stitches I had sewn.

She gasped when she opened the box and saw them.

“I don’t know if they’re any good,” I said. “They’re probably way too soft. I had no idea what I was doing.”

But while I was still protesting, she flung her arms around me. We clung together for a long second and then we both leapt back. These days our bodies carry our sorrows as though they were bowls brimming with water. We must always be careful; the slightest jolt or unexpected shift and the water will spill and spill and spill.

Eva’s gift to me was this notebook.

“It’s not a computer,” she said, as I lifted it from its wrinkled wrapping paper, recycled from some birthday long ago and not yet sacrificed as fire-starter. “But it’s all blank, every page.”

“Blank paper!” I marveled. “Where on earth did you get it?”

“I found it behind my dresser. It must have fallen back there years ago. I thought you could use it to write about this time. For our grandchildren or something.”

Right now, grandchildren seem less likely than aliens from Mars, and when I first lifted the stained cardboard cover and flipped through these pages, slightly musty, and blank except for their scaffolding of lines, I have to admit I was thinking more about studying for the Achievement Tests than about chronicling this time. And yet it feels good to write. I miss the quick click of my computer keys and the glow of the screen, but tonight this pen feels like Plaza wine in my hand, and already the lines that lead these words down the page seem more like the warp of our mother’s loom and less like the bars I had first imagined them to be. Already I see how much there is to say.

France

Into the Forest was translated into French by Josette Chicheportiche and published by Editions Gallmeister in January, 2017. Dans la forêt quickly became a bestseller in France, selling over 200,000 copies within the first five years. Jean has enjoyed meeting many booksellers and readers on her book tours in France, Belgium, and Switzerland.

A highly acclaimed Audiolib version, narrated by Maia Baran, was released in 2019.

Listen to Jean’s interview with David Collins on Radio France:

LES LIBRAIRES EN PARLENT:

Un livre qui renvoie à une grande humilité de l’espèce humaine face à la nature. Un très beau livre.

Une éblouissante ode humaniste pleine de poésie, d’espoir et surtout d’amour !

L’Oiseau moqueur – Sucy en Brie

Un roman haletant écrit dans une langue sensuelle. Un chant d’amour, manifeste pour une autre vie. Un coup de cœur !

Librairie de Port Maria – Quiberon

Un livre bouleversant, charnel et entêtant. Un choc.

Un texte doux et mélancolique […]. Une lecture engagée, puissante et émouvante. Un délice!

L’homme n’est rien, et si vous en doutez, lisez ce livre. Un livre magnifique !

Le Livre et la Tortue – Issy-les-Moulineaux

Ce livre écrit il y a 20 ans percute de plein fouet notre temps, l’oblige à s’interroger. Et le fait de magnifique manière.

Magnifique et bouleversant roman !

L’écriture poétique et le sujet traité de façon tout à fait originale – le roman est paru en 1996 aux États-Unis – en font un très beau texte, puissant et hypnotique.

Au Moulin des Lettres – Épinal

Un récit magnifique, dur, fort […]. Un récit de nature writing dans les règles de l’art, où l’humain se plie à la Nature et non l’inverse… !

300 pages époustouflantes de beauté. Un récit organique, animal, végétal, charnel, sensuel et puissamment humain sur nos capacités de résistance. Déstabilisant et rassérénant à la fois.

Lentement, au fil des pages, tous nos sens sont en éveil. On se sent capables de danser sans musique et de lire l’index d’une encyclopédie, comme les deux héroïnes, qui découvrent les soirées aux chandelles.

Avec une puissance étonnante, le lecteur va être kidnappé pour se retrouver lui aussi dans la forêt. Lentement, au fil des pages, tous nos sens sont en éveil.

Une prose très belle. C’est court, mais très efficace. Le roman est porté par l’énergie des deux gamines, on est porté par l’espoir.

Un roman époustouflant.

Sublime !

Tropismes – Bruxelles – Belgique

Un choc littéraire, il y a une grande force poétique dans ce livre.

Roman surprenant de Jean Hegland qui interroge avec intelligence et finesse la fragilité de notre civilisation : UN CHOC !

C’est lent, prenant, on s’attendrait presque à voir surgir des zombies ! Ce roman nous tient en haleine jusqu’au bout.

C’est un magnifique roman d’apprentissage, un très grand en fait. J’ai aimé, beaucoup beaucoup. Et c’est superbement traduit par Josette Chicheportiche.

Ce roman est un vrai bijou de poésie. C’est formidable.

Le Passeur de l’Isle – L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue

Entre récit initiatique, introspection, roman survival, découverte de l’animal en soi, écoute de ses instincts, de sa nature profonde, de femme, de mère, de soeur, de la force du lien et de l’amour…. Ce roman avait tout pour me plaire: il m’a subjuguée!

L’écriture simple et juste, les très belles images de la nature et les descriptions puissantes des liens qui unissent ces deux sœurs offrent au lecteur un beau retour vers l’essentiel.

L’écriture est à la fois forte et sensible, lumineuse et sombre… Bref, les mots manquent… Peut-être parce que c’est tout simplement une magnifique histoire, et qu’il n’y a rien à ajouter.

Une belle ode à la nature, pleine de sensibilité, à la fois puissante et délicate.

Une magnifique fable écologique qui nous incite en cette année la plus chaude de l’humanité à faire la paix avec cette nature qui tient entre ses mains les clés aussi bien de notre fin que de notre salut.

Le souffle poétique et la puissance de l’écriture de Jean Heglanddonnent une force incroyable à ce roman digne du livre cultissime de Marien Haushofer Le mur invisible. À lire et à faire lire de toute urgence!

Dans la forêt serait presque une synthèse des différents chemins empruntés par les éditions Gallmeister. Roman d’anticipation et d’évasion qui vient flirter avec les thématiques survivalistes, c’est tout autant un texte pétri d’humanisme pour traiter de la tendresse qui unit cette famille. Dans la lignée de Thoreau, Jean Hegland propose avec finesse un transcendantalisme de la nécessité, soit la réconciliation des hommes et de la nature comme destinée salvatrice de nos sociétés.

Un huis clos entre deux soeurs et la forêt, quand tout signe de civilisation a disparu… ce roman est magnifique !

L’Oiseau Lire – Visée – Belgique

Un roman poétique, poignant, d’une criante actualité, qui délivre un message essentiel ! Un coup de cœur de cette rentrée.

La force de ce roman, c’est que tout au long de leur histoire, nous sommes avec elles, au plus près.

Magnifique roman d’apprentissage, de rebellion, de découverte de soi.

Ce roman de survie dans la forêt dose au centimètre le degré de précision technique nécessaire pour faire partager à la lectrice ou au lecteur l’angoisse du lendemain comme l’insouciance comique et tragique à parts égales de l’adolescence logiquement habituée à remettre son sort matériel entre les mains d’adultes protecteurs.

Un roman très sensible et poétique, une ode puissante à la nature ! Énorme coup de cœur !

La Fleur qui pousse à l’intérieur – Dijon

Ce livre est somptueux par son écriture, par tout ce qu’il véhicule : retour à la Nature et aux liens humains.

Ce roman est une perle du Nature Writing. Une plongée saisissante, âpre, sensuelle dans le quotidien de ces deux sœurs, alors que le monde s’écroule sous le poids de ses excès. Un choc littéraire et une nouvelle pépite de Gallmeister.

Se dire qu’on aurait pu passer à côté d’un livre aussi magistral fait froid dans le dos. Heureusement, il n’en est rien, on peut désormais se jeter dessus et l’offrir à tout le monde. Et ça, c’est vraiment bien.

Filigranes Corner – Bruxelles – Belgique

Franchement, si on se demande assez vite comment Nell & Eva pourront s’en sortir dans un monde comme celui-là ; ici, en francophonie, on se demande maintenant comment on a pu se passer d’un roman aussi grand, et puissant, que celui-ci.

Librairie du Midi – Oron-la-Ville – Suisse

Une fable écologique percutante qui offre un regard lucide sur notre mode de vie.

Le Grenier d’Abondance – Salon-de-Provence

Ce texte est un premier roman écrit il y a 20 ans. Est-ce prémonitoire ou conjuratoire ? Il est magnifique et à lire de toute urgence.

Gros coup de cœur pour ce texte empreint de sensibilité, de poésie, de justesse et d’émotion !

Il est encore tôt mais il y a fort à parier que nous ayons là LE grand roman de cette nouvelle rentrée littéraire d’hiver !

Ce n’est pas un texte qui vous épargne. C’est tout l’inverse : le genre de livre qui touche quelque chose en vous, quelque chose de difficile à dire, intime, sensuel, profond. C’est un livre de silences, de danse, de mots et de bêtes. Et c’est un putain de grand livre.

Un petit chef d’œuvre de littérature de survie en milieu sauvage ! Un apprentissage de la forêt, de l’environnement et de soi-même tout à la fois douloureux et vibrant, rugueux et touchant.

Il y a, entre ces lignes, tellement de beauté, de sensualité et d’amour qu’il est difficile de trouver les mots pour l’exprimer. Si vous lisez le grand roman de Jean Hegland, vous serez enchanté : C’est la plus belle promesse littéraire de ce début d’année.

Dans la forêt est un chef-d’œuvre.

Filigranes – Bruxelles – Belgique

Plus de vingt ans après, le texte est criant d’actualité et juste, si bien qu’on y plonge en apnée pour n’en ressortir – et pas indemne – que 300 pages plus tard. C’est un texte saisissant, aussi bouleversant que bienveillant, sur la solitude, sur la force de l’humain mais surtout sur la force de cette relation familiale qui triomphe des disputes, des désaccords, des imprévus, de l’exiguïté.

Éblouissant ! Un livre magnifique, plein de poésie, d’espoir, dans un monde voué au chaos. Un immense coup de cœur.

Librairie du Hérisson – Montargis

Magnifique et intimiste récit fait de flash-backs et des réflexions nubiles de Nell, Dans la forêt est une œuvre de nature writing dense et profonde, qui donne davantage envie de connaître le monde qui nous entoure que d’effectuer un stage de survie préventif.

ABSOLUMENT MERVEILLEUX! Énorme coup de cœur pour ce roman exceptionnel ! La découverte de ce début d’année !

Sensualité, nature sauvage, ce premier roman de Jean Hegland est bouleversant et envoûtant. Une pépite à ne pas manquer !

Attention chef-d’œuvre ! Un roman de toute beauté, à l’écriture puissante, où la poésie, la beauté des paysages, la fraternité, la force de vivre croisent la peur, l’âpreté, la violence et la mort. Splendide !

2017 n’a pas encore commencé que j’ai déjà l’impression d’avoir lu le futur livre de l’année. Le cul entre deux chaises, de savoir si ce roman pillone La Route de McCarthy, apporte un peu plus de verdure à La Constellation du chien de Peter Heller. Comme si Jean Hegland avait choisi de raconter ce qui s’était passé avant que Jack London n’écrive La Peste Écarlate.

Vous dire d’abord que lorsque j’ai refermé cet ouvrage, j’ai aussi fermé les yeux et versé ma larme. Pas une larme de tristesse, une larme d’intense émotion plutôt. Dans la forêt est un écrin dans lequel il est nécessaire de se perdre. […] Si il y a un livre à acheter le 03 Janvier 2017, ce serait celui-là, indéniablement.

Le monde se délite. Après la mort de leurs parents, Nell et Eva vont être confrontées à la survie. À travers le journal de Nell, nous découvrons petit à petit à quoi correspondaient leur vie, leur famille et leurs rêves.